A look at our heritage: how philosophy questions our ways of thinking, acting and living together

- Science and society

- Research

on the November 4, 2025

To mark World Philosophy Day on November 20, (re)discover the views of Mélanie Plouviez, researcher at the Centre de Recherches en Histoire des Idées (CRHI) - Université Côte d'Azur, through an article in Intervalle magazine.

Philosopher Mélanie Plouviez explores how philosophy questions our ways of thinking, acting and living together. In this article, she shares her work on heritage.

It's a good opportunity to recall how philosophy helps to shed light on today's major issues - be they ethical, political or technological.

INHERITANCE SQUARED: SOCIAL JUSTICE?

Inheritance is a family gesture. A parent bequeaths a house, savings, land... But it is also - and this is too often forgotten - a political, economic and philosophical act. Inheriting is not just about receiving: it's about participating in the way wealth is distributed in society. And this question is much more burning and topical than it seems...

As economist Thomas Piketty has shown, inheritance came back into the spotlight in the 1970s. In France, a growing proportion of assets

no longer acquired through work or savings, but through family inheritance. A phenomenon that brings us closer to the societies of the 19th century, times we thought were over. Back then, inheritance was mentioned everywhere: in newspapers, in parliamentary debates, in leaflets.

parliamentary debates, in political leaflets. Its legitimacy was seriously debated, and above all: people weren't afraid to challenge its evidence.

In 1920, an Italian thinker, Eugenio Rignano, put forward an idea that was to make waves: inheritance tax should increase the further an asset was passed down from generation to generation. Clearly, the more wealth has been inherited (and re-inherited), the more heavily it should be taxed. The idea is simple: "recycled" wealth is taxed more heavily than newly acquired wealth. Inheritance squared, in short! In other words, not all inheritances are created equal. Inheriting directly from one's parents, or reclaiming a castle that has passed through six generations, is not the same thing. With this system, Rignano wants to modulate the legitimacy of transmissions according to their distance, not geographical, but temporal.

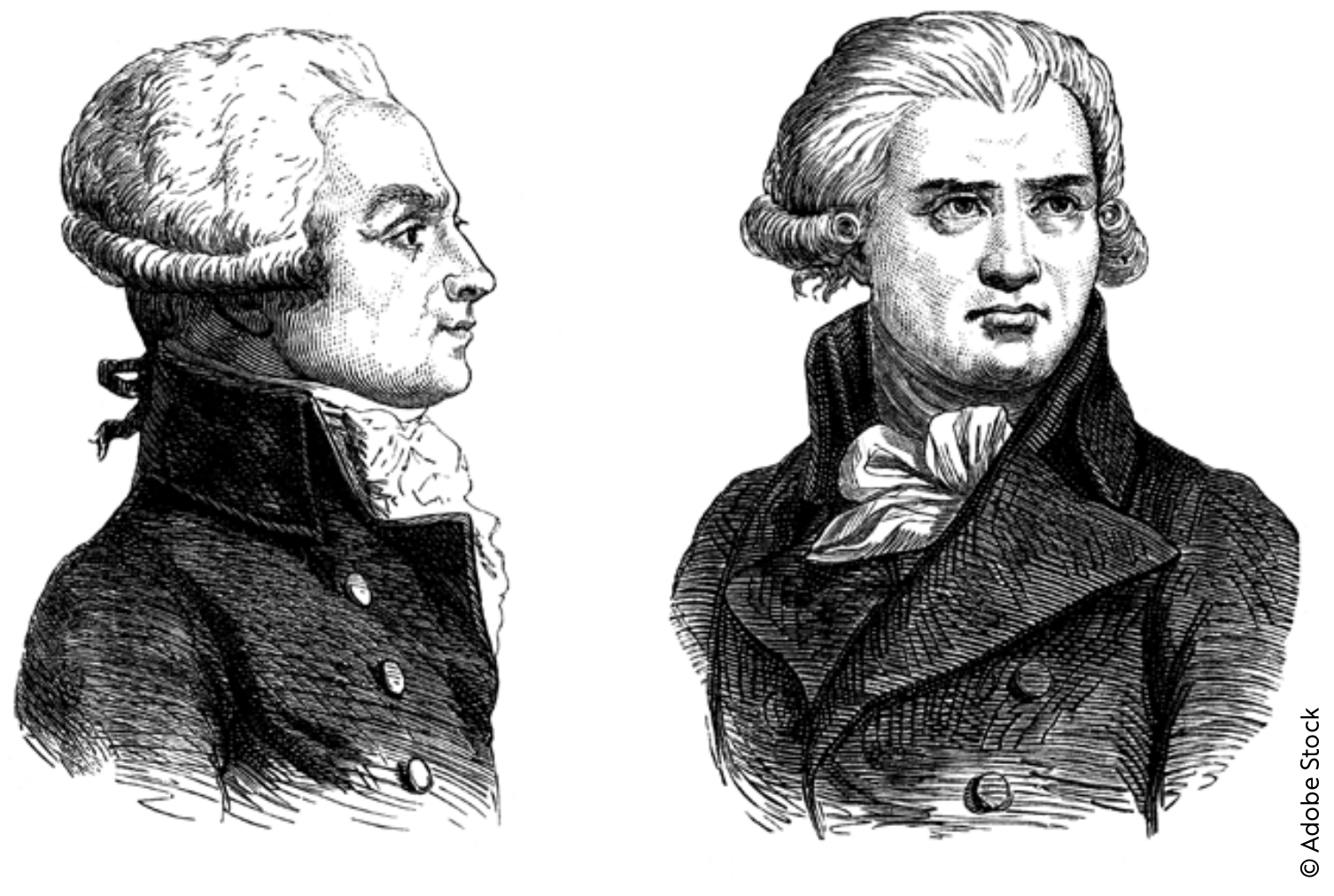

In the 19th century, this was not so obvious. Figures such as Mirabeau and Robespierre saw inheritance as an opportunity for society to decide what to do with the property left behind by the dead. Robespierre asserted: "Property is sacred only insofar as it is the fruit of labor. "The heir, on the other hand, has often done nothing to acquire what he receives.

Today, we tend to take family inheritance for granted, as a natural act. Why not take a fresh look at this institution? This is precisely

PHILHERIT project, supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche and Université Côte d'Azur. With the help of digital humanities, two researchers, Stephania Ferrando and Mélanie Plouviez, together with Pierre Carl-Langlois, researcher at the University of Montpellier de Montpellier 3, explored over 100,000 texts between 1780 and 1920, digitized on Gallica, to find traces of forgotten debates on heritage.

And surprise! Numerous thinkers - sociologists, philosophers, MPs - supported the idea that inheritance could be transformed to reduce inequalities. For them, it was not simply a private right, but a tool for social justice.

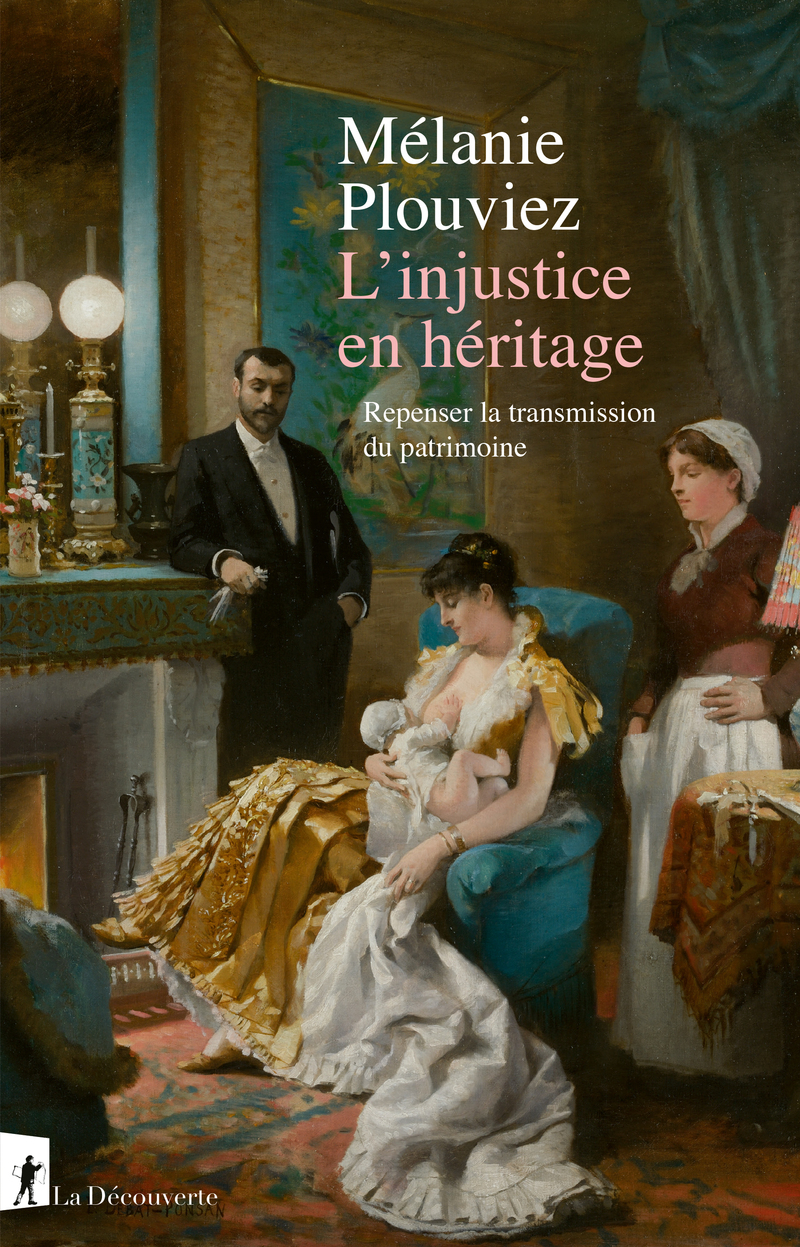

L'injuste en héritage by Mélanie Plouviez published in 2025 by La Découverte.

INHERITANCE LAW, A LITTLE-KNOWN LEVER

A decisive turning point was reached between 1791 and 1794, when the revolutionaries, aware of what was at stake, introduced the first modern rules of succession. Robespierre was already advocating an inheritance law in the service of equality, capable of limiting the cumulative effects of family wealth.

And it's not just a matter of principle. A study carried out in Denmark has shown that the performance of companies falls by 20% after they have been passed on to the founder's children. What if inheritance isn't always the best solution, even economically? Some 19th-century utopias, such as those of the Saint-Simonians, went even further: on the death of the owner, property was to be reallocated by a democratic public body to those who knew how best to use it.

"Can man's property extend beyond life? Can he give laws to his posterity, when he is no more? Can he dispose of the earth he has cultivated, when he himself has been reduced to dust? No" - Robespierre

In France, the French Revolution marked a turning point with the abolition of feudal privileges. The Napoleonic Code consolidated this evolution by unifying inheritance practices and imposing the division of inheritance among all children. It severely limited individual choices in favor of family equality. Contrary to popular belief, you can't do as you please with your assets, even during your lifetime!

In 2025, the average age of inheritance is... 60. In other words, inheritance no longer helps young people get started in life. In 1820, people inherited at around 25. But what about tomorrow? Between now and 2040, 9,000 billion euros will be passed on in France, mostly between people who are already elderly and often already wealthy. In this context, asking the question of inheritance means asking the question of social justice. Who receives? Who gets it? Who receives? And in the name of what?

Far from being a simple family ritual, inheritance is a social institution that profoundly shapes our societies. By questioning the past, and re-reading the debates of the 19th century, the PHILHERIT project invites us to suspend the obvious and consider other ways of passing on wealth. So, are you ready to inherit... a new way of looking at things?

THE PHILHERIT PROJECT

PHILHERIT is an interdisciplinary project involving philosophy, law and economics. It explores the links between inheritance and social justice, through a historical and normative analysis of successive theories of inheritance, from 1800 to the present day. The aim is to rethink the principles governing the regulation of inherited wealth, and to establish a dialogue between past, present and future. This article was written as part of the ANR SAPS Côte d'Azur project, which provides scientific mediation for research projects funded by the ANR in 2021.

To read other articles from Intervalle magazine: https://science-societe.univ-cotedazur.fr/intervalle-le-magazine